Spinal Conditions: Spinal Stenosis and Spondylolisthesis

Spinal Stenosis

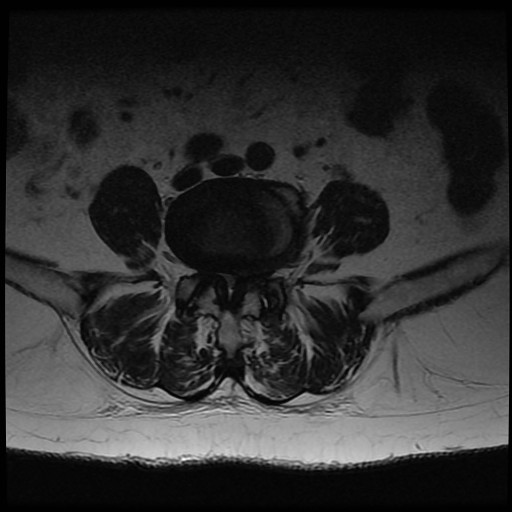

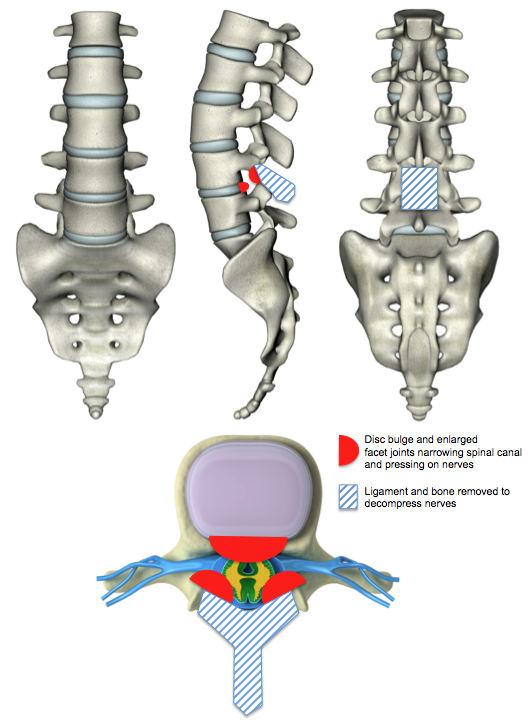

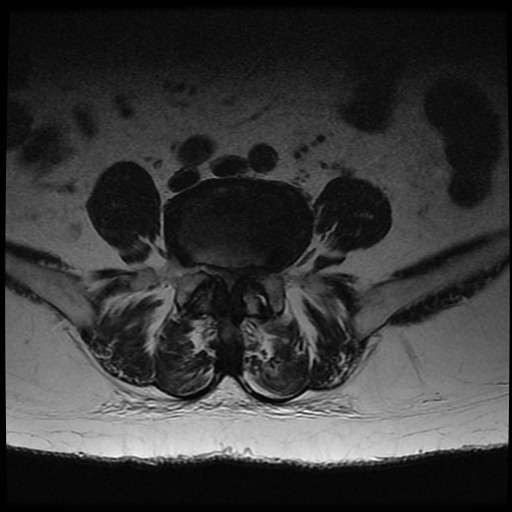

Spinal stenosis is a condition in which there is narrowing of the spinal canal and therefore a reduction in space for the nerves. It is usually due to degenerative changes (acquired). The intervertebral disc can be thought of as a car tyre - over time it deflates and bulges. As this occurs the height is lost at the front of the spine and the facet joints at the back of the spine start to take more load. Facet joint degeneration then occurs and the joints and ligaments can enlarge. The ligaments at the back of the spine tend to buckle inward as the disc height is reduced and they become lax. Narrowing of the spinal canal and space for the nerves then occurs due to a combination of the disc bulge, facet enlargement (hypertrophy) and ligament buckling (ligamentum flavum hypertrophy). Spinal stenosis can also be present from birth (congenital) due to a smaller spinal canal.

Spinal stenosis typically gives leg symptoms due to nerve compression. Back pain symptoms are generally due to the underlying degenerative changes that have taken place and their management is discussed in the low back pain section. Occasionally when decompressive surgery is performed for leg symptoms in patients with spinal stenosis the back pain can improve but this is unpredictable. Surgery for back pain alone in spinal stenosis is rarely performed.

Patients with degenerative spinal stenosis are typically older than those suffering from a disc prolapse. They typically complain of tiredness, heaviness and discomfort in the legs when walking or standing. It generally affects the buttocks, thighs and upper legs first before moving down to the lower legs, calves and feet. The distance they can walk before the symptoms start can often vary and they find that leaning forward, sitting or even crouching relieves the symptoms. They often find that they can walk up a hill or cycle for unlimited periods. This is because the spine is flexed in these positions and the size of the spinal canal is increased. Some patients can only go shopping with the use a shopping trolley and they find themselves bending forwards leaning on the trolley in a flexed position to relieve their symptoms. Activities in which the spine is in extension, such as walking down a hill or prolonged standing, worsen the symptoms. Bladder and bowel dysfunction can occur in spinal stenosis but fortunately this is uncommon (cf Cauda Equina Syndrome). Medical professionals call the symptoms that are due to spinal stenosis neurogenic claudication. In contrast, patients with vascular disease in the legs, such as narrowed blood vessels, suffer from vascular claudication. They typically describe cramping or tightness in the calf associated with walking. It rarely occurs when they are standing still and the distance that they are able to walk before the symptoms start is the same. The symptoms do not vary with posture and they find that they are unable to walk up hills or cycle. Occasionally they get cramps in the calves at night that is only relived by hanging the leg out of the bed.

Treatment and Outcomes for Spinal Stenosis

The natural history of untreated degenerative spinal stenosis is that 15% improve, 30% deteriorate over two to three years to the extent that surgery is deemed necessary and 45% remain static over time. Conservative treatment in the form of analgesics, core trunk stability exercises, physiotherapy, injection therapy etc should always be considered before invasive surgical procedures. Surgery is indicated when:

- Conservative treatment has failed

- There is intractable leg pain

- There is progressive neurological deterioration (e.g. worsening weakness)

- Cauda equina syndrome

Overall, the outcomes from surgery for degenerative spinal stenosis are good and up to two thirds of patients can expect good to excellent long term results. However, 25-40% are not satisfied and up to 20% may require further surgery. In contrast, 50-60% of patients who are managed non-operatively are not satisfied.

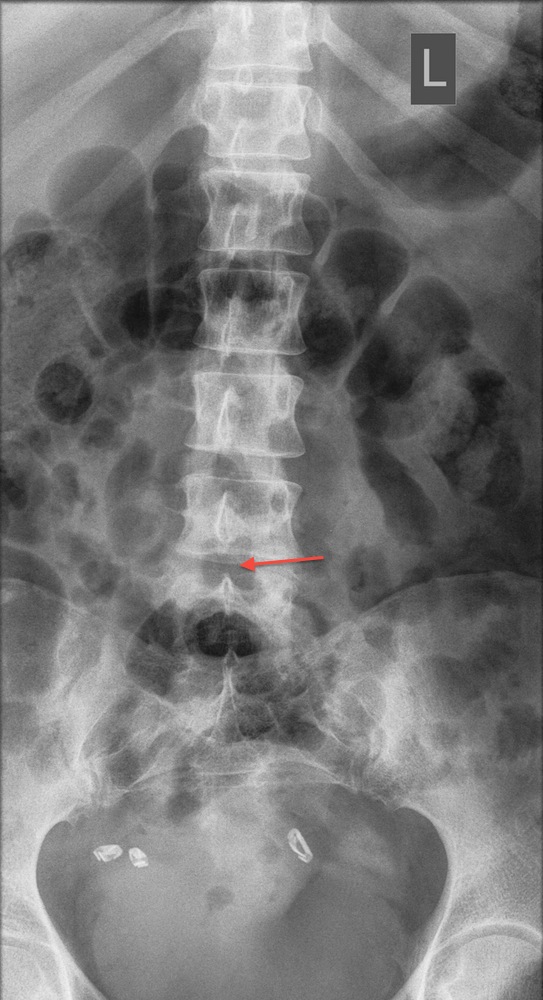

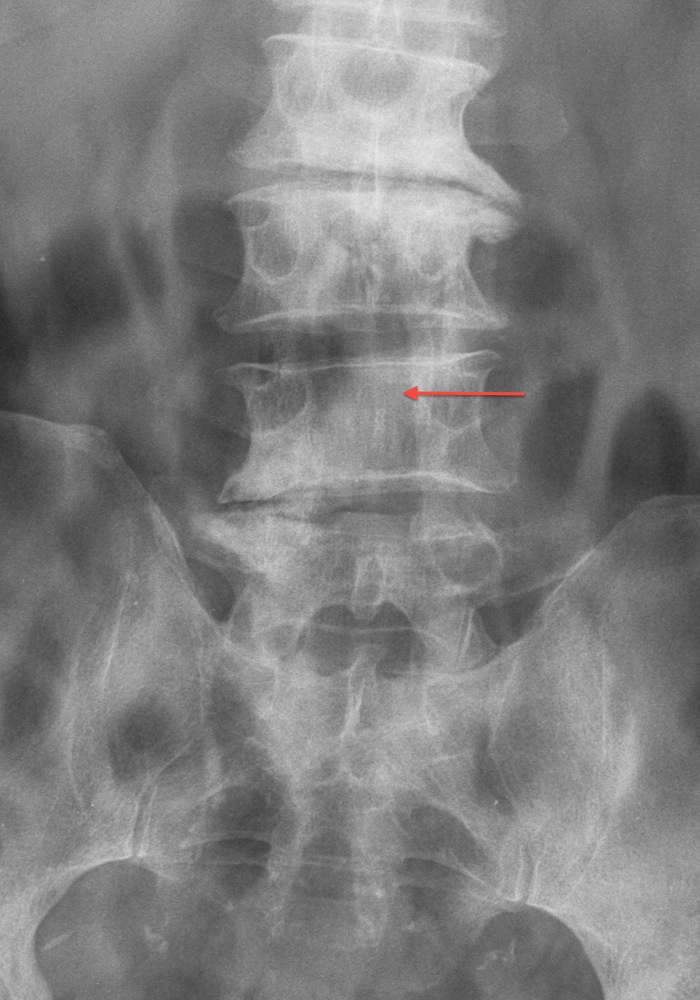

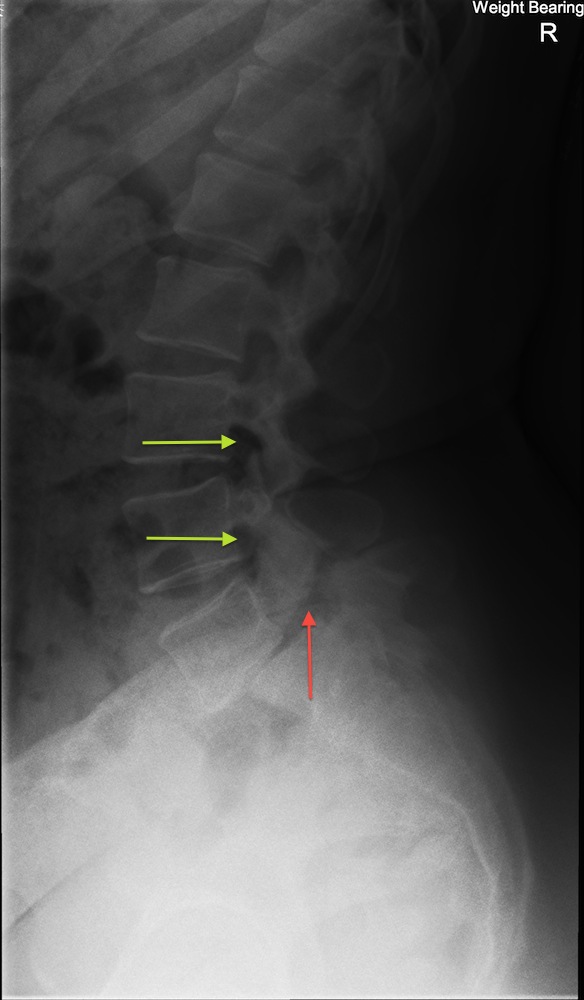

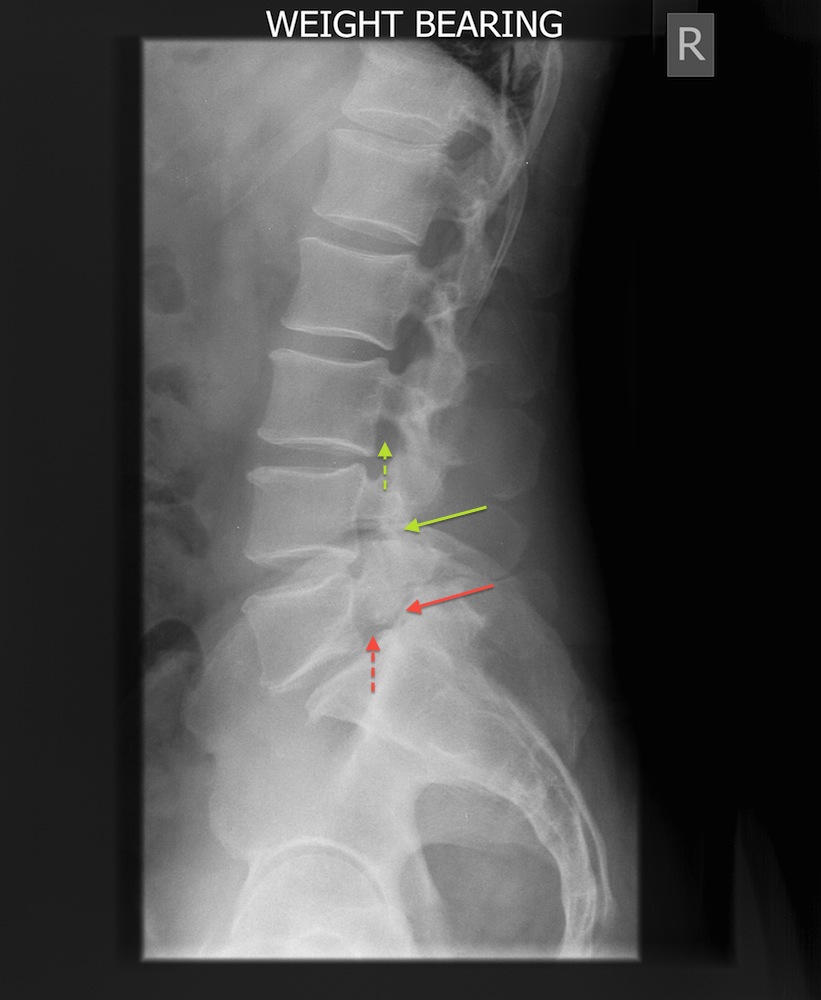

Spondylolisthesis

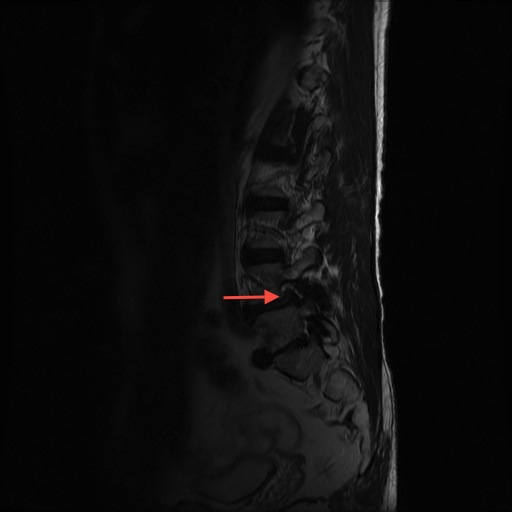

Spondylolisthesis is a slippage of one vertebra on another. Not infrequently the degenerative ageing process in the spine can result in a spondylolisthesis. This is called a degenerative spondylolisthesis. As the disc height narrows and the facet joints become worn, the joints between two vertebrae can become lax and one of the vertebra can slip forwards or backwards a small amount in relation to the other. The spinal canal can become narrowed (stenotic) and nerve symptoms in legs can occur from compression in the narrowed spinal canal and narrowed neural foramens (the place where the nerves exit the spine). The majority of symptoms are the same as those in spinal stenosis section described above. Back pain can also occur because of the abnormal motion and position of the vertebrae. Occasionally, patients describe a clunking and clicking sensation in the spine when they move into certain positions. Spondylolisthesis can also occur when there is a spondylolysis and subsequent disc degeneration (a spondylolytic spondylolisthesis). This is described below. Spondylolisthesis has been classified into 6 types:

- Congenital or dysplastic – this is when there is a developmental abnormality in the spine resulting in a slip of one vertebra on another

- Isthmic or spondylolytic – this is when there is a defect in the pars interarticularis part of the spine

- Degenerative – described above

- Traumatic – this is when the slip has been caused by a traumatic fracture (break) in the bone

- Pathological – this is when a disease process in the spine has caused the slip (e.g. a tumour)

- Postsurgical – this is when the slip has occurred because of previous surgical interventions on the spine

Treatment and Outcomes for Spondylolisthesis

The treatment of spondylolisthesis depends on the cause and on the patients’ symptoms. In general, operations to relieve nerve symptoms due to nerve compression in the form of decompression are very successful. However, as a vertebra has slipped forward, removal of bone to decompress the nerves can result in further forward movement and this can lead to more problems. It is for this reason that surgeons tend to fuse that segment of the spine at the time of decompression, thereby preventing this from occurring.

Fusion procedures for spondylolisthesis can improve low back pain. This is more predictable than a fusion procedure for degenerative disc disease. It is, however, less predictable than a decompression procedure for compressive nerve symptoms in the legs. The reason for this is that the vertebrae have moved into an abnormal position and may be moving in an abnormal fashion. Stopping the abnormal movement is thought to reduce the back pain.

A fusion procedure when decompressing spinal stenosis is indicated when there is:

- A spondylolisthesis

- Recurrent stenosis

- Iatrogenic instability

- Deformity – a scoliosis or kyphosis is present

- Pre-operative instability – abnormal motion is present

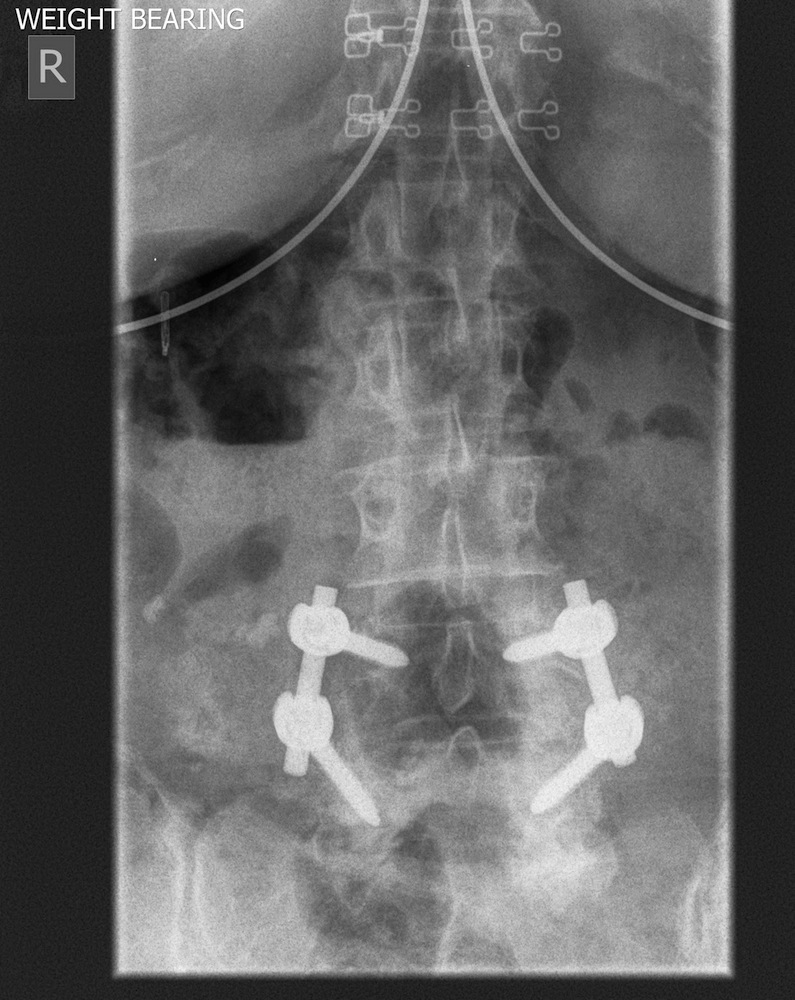

Fusion is used to relieve back pain and eliminate instability. When a fusion is performed it can be done with or without the use of stabilizing implants (such as screws and rods). Stabilization is used to promote the fusion and correct any deformity.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is the commonest form of slip and its natural history (or non-surgical management) is reasonable. In the absence of any neurological deficits the majority of patients do well with conservative management. The majority (75%) of patients do not develop any neurological deficits (e.g. weakness). However, 80% of those patients who present with a neurological deficit such as weakness will tend to get worse over time. One third of the slips progressively increase in size but this does not correlate with clinical symptoms. As the disc space narrows it has been shown that any low back pain tends to improve (there is less abnormal movement). Over a four-year period, 30% - 50% of patients managed conservatively for degenerative spondylolisthesis undergo surgery for persistent or worsening symptoms.

Surgery is indicated when there is failure to improve with conservative non-operative measures or there is deterioration in symptoms. Patients who present with sensory changes, muscle weakness or cauda equina syndrome tend to decline without surgery. Decompression with fusion in degenerative spondylolisthesis tends to be associated with better outcomes. Instrumentation (e.g. screws and rods) improves fusion rates but also increases the complication rates.

70% of patients undergoing surgery for degenerative spondylolisthesis report a major improvement in their symptoms compared to 25% of those having non-operative treatment. On average surgical decompression and instrumented fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis halves the pain (both in the back and the leg) and doubles the walking distance.

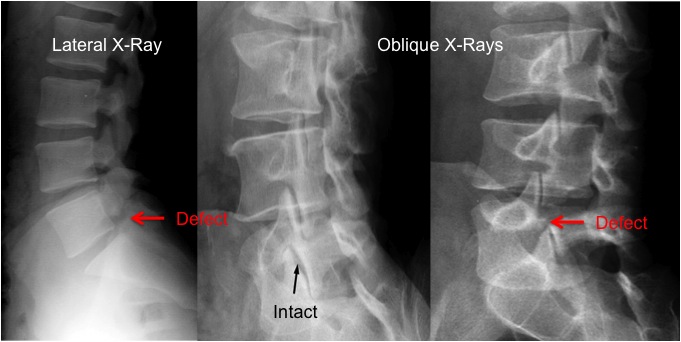

Spondylolysis and Spondylolytic Spondylolisthesis

A spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis part of the spine. It is present in around 5% of the population and is often asymptomatic. It is most commonly thought to be due to a growth and development problem during childhood and adolescence, although there can be other causes. It is frequently associated with activities that involve hyperextension of the spine (bending backwards) such as high diving, trampolining, gymnastics, fast bowling, wrestling and weight lifting. It can lead to low back pain of a similar nature to facet joint pain (see low back pain section).

With degeneration of the spongy intervertebral disc, a forward slippage of one vertebra on the other can occur. This can result in nerve irritation and leg symptoms as well as back pain.

The mainstay of treatment for spondyloysis is non-surgical, and with avoidance of activities that precipitate the pain. Injections of local anaesthetic and steroid into the defect can be performed to confirm the source of the pain and also to help treat it by reducing any inflammatory component. Failing this, surgery can be performed in younger patients to repair the defect. In older patients surgery is often in the form of a fusion procedure.

We do not know which patients with a spondylolysis will go on to develop a symptomatic spondylolisthesis later in life. Prophylactic surgery for an asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic spondylolysis is not recommended. There is no evidence that interventions will prevent the development or slow the onset of a lytic spondylolisthesis. However, it is known that some patients with symptomatic spondylolytic spondylolisthesis benefit from weight loss, physiotherapy and core trunk stability exercises. The indications for surgery in spondylolytic spondylolisthsis are the same as those for spinal stensosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis described above.

Further Information on Stenosis and Spondylolisthesis

More information on stenosis and spondylolisthesis can be found in the following documents and in the Useful Links section of this site. Please note that some of these documents are written for health care professionals.

Information on spinal stenosis from Patient.co.uk

Information on spondylolisthesis from Patient.co.uk

Patient information from the British Association of Spinal Surgeons

Patient information from the North American Spine Society

Stenosis Option Grid: this can help make choices for those suffering from this condition